Welcome to the second issue of our new newsletter. We are excited to have the lead article written by Beth Ann Eberle, a student at New Mexico Tech working on her MS degree. Her work is an example of the many kinds of scientific information we now need to manage the state’s water more effectively. New Mexico is lucky to have three major higher educational institutions focused on water and training the new scientists and water experts we need to move into an uncertain future. We hope to continue introducing all of us to the issues facing New Mexico as well as to our new scientists and water experts.

Contents

- Hydrologic Assessment of the NM Salt Basin Region by Beth Ann Eberle

- Panel: Science-Based Planning for Resilience There Was Always Less Water – John Fleck by Kathy Grassel

- Panel: Science-Based Planning for Resilience Resilience Begins with Data – Stacy Timmons by Kathy Grassel

- Panel: Science-Based Planning for Resilience Late to the Game: A Native Perspective – Darryl Vigil by Kathy Grassel

SAVE THE DATE

January 13–14, 2021

New Mexico Water Dialogue

27th Annual Statewide Meeting

Hydrologic Assessment of the NM Salt Basin Region

By Beth Ann Eberle, New Mexico Tech

The Salt Basin is a 5,000 square mile closed basin shared by southeastern New Mexico and northwestern Texas. This basin has an extensive history of hydrological studies. The on-going research project funded by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is intended to evaluate the groundwater availability in the Salt Basin, help assess the local sustainability of current groundwater usage, and indicate the implications for future development.

My name is Beth Ann Eberle, and I am a student at New Mexico Tech. In addition to my rigorous course load for my MS degree, I am part of a group of researchers from NMT Hydrology Program and from the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources (Aquifer Mapping Program). The two-year project, that will hopefully be completed in 2021, is intended to fill data gaps with geophysical analysis and new data collection, expand and update a groundwater model, and improve the understanding of the regional water budget. For my part of the project, I am using hydrochemical data and analysis to refine estimates of the quantity and quality of recharge to the groundwater system, which will help to evaluate future water usage stability.

This means I need to have all of the groundwater chemistry data that is available throughout the basin for my analyses. All of the major and minor ion concentrations, field conditions, associated geologic units, and previous groundwater age-dating results are required for my chemical analyses. There are over 900 wells throughout the Salt Basin. That means there are over 900 data points, with more coming in as new data is collected. All of this data was spread out among hundreds of papers many of which were written before 2000. I read most of those hundreds of papers to check for relevant material. This was time-consuming, but eventually proved to be useful when it came to writing a summary of previous hydrochemical research and associated recharge estimates for an open-file report about the Salt Basin published by the NMBGMR.

For the chemical analysis component, I needed to learn Python coding and how to use a few pre-made programs to utilize the hundreds of data points. I have no formal training on coding, so it was a challenge to learn the new language and understanding what the results actually meant. Now that I have learned Python and the basic hydrochemical analysis is done, I am working to separate out specific basin areas or flow paths to actually estimate groundwater recharge.

To make this project just a little bit more difficult for me, the Salt Basin is in southeastern New Mexico. I am in central Pennsylvania, more than 1,800 miles and two time zones away. I was at NMT up until March 2020 and have been stuck in PA ever since the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine began. This has posed a few more challenges than I expected for the project. I cannot be present to collect new water samples from the Salt Basin. I have never actually been to the study site that I am researching. Simply sharing or moving data across the country has its limits. And trying to coordinate meetings with a project group two time zones away is even more difficult than trying to schedule a meeting with a group two doors away, but luckily our research team has weekly group meetings.

Overall, the Salt Basin project is going relatively smoothly and we are on track to complete the project in the summer of 2021. I have a spreadsheet with all 900 some data points; I have presented at an unofficial online conference; I contributed to a published open-file report; and I now know how to code in Python. Trying to gather all of the available data and work through a pandemic is not the easiest thing to do. Nonetheless once you have all of the data, it is still possible to reach new conclusions with old data. I look forward to the conclusions of this research and seeing it used for the benefit of the Salt Basin.

For more information and updates on the project, refer to: https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/resources/water/projects/home.cfml?id=98

Our thanks to departing board member

Katherine Yuhas.

Welcome to new board member Denise Rumley.

Panel: Science-Based Planning for Resilience

There Was Always Less Water – John Fleck

by Kathy Grassel

The University of New Mexico

John Fleck is a professor and Director of the Water Resources Program at UNM following many years as a newspaper reporter writing about water. He also continues work on the Colorado Basin issues and is the author of two books about the Colorado. Fleck, always one to look on the bright side of life, is a regular at Dialogue meetings and manages to offer some glad tidings in this changing world of hand-wringing about our water future. His potent example of resilience in action actually took place a decade ago in Las Vegas, Nevada—“the best explanation for me of how resilience in municipal water management works,” Fleck begins. For his Colorado River research work, he was visiting the Southern Nevada Water Authority, the water authority that serves Las Vegas. Las Vegas gets its water from Lake Mead from pipes that go out into the lake. There’s a point when the elevation of the lake goes low enough that Las Vegas and its two million people can’t get water anymore. “That is the threshold and the tipping point where you can clearly identify and understand the concepts of resilience,” Fleck says. “The Water Authority spent $1.5 billion and moved their intake lower so when the lake drops, they can still get water.” Having spent $1.5 billion, they haven’t needed it, but they have bought themselves some resilience.

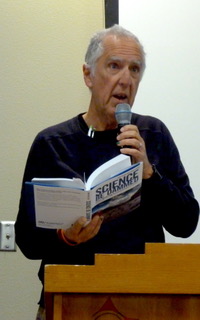

So how did we get into this pickle in the first place? It goes back to the negotiation of the Colorado River Compact of 1922 that divvied up the water among seven basin states. This is the subject of John Fleck’s latest book, co-authored with Eric Kuhn, cleverly named, Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River. It’s about the history and origins of the Colorado River Compact and how science was buried in favor of development boosters resulting in the overallocation of the river’s waters and causing all the fights we’re having these days. Fleck and Kuhn were reading mind-numbing tracts of congressional hearings and came across a USGS hydrologist named E.C. LaRue. He was a Colorado River hydrologist in the 1920s and presented his findings to Congress that the river’s annual flows were insufficient to pull off the project. The compact commissioners sidelined him and now here we are.

“There’s the conventional story that’s been told, including by me, about how the allocation of Colorado River water happened. They only had stream gages measuring flows of rivers for about 20 years and we know that the 20-year period on which the compact was based was an unusually wet period. How could they have known that it was an unusually wet period, what rotten luck?” What Fleck and Kuhn found was in fact there were scientists at the time who did know. They warned that there had been significant droughts in the late 1800s and that the water supply that they were banking on was not sufficient to meet the allocations. “What Eric and I do in the book is follow this kind of thinking forward across the 20th century, as scientists like LaRue, Herman Stabler, and General Sivert all kept saying the same thing,” Fleck says. “The science kept compounding and compounding, and the willful ignorance continued. We ended up in the situation we are in today.” Fleck reminds us that the augmentation from Colorado water that we get here from the Rio Grande has become critical to meeting our needs, “so we are entrained to this large-scale problem that we have in the Colorado River Basin.”

What do we need to need to do now planning for our futures? “Paying attention to the science is not just a matter of hydrology. It’s paying attention to what the humans are doing with the water,” Fleck says. “The widespread presumption that population growth means growing water demand drives much of the politics of water planning in the Colorado river basin, but it is wrong. We are consistently using less water in almost all the municipal areas despite population growth.” He continues that water use in the basin’s major agricultural regions also is going down, even as agricultural productivity continues to rise.

Fleck acknowledges that his assumed role as optimist at these meetings can be challenging in the face of unnerving climate scenarios that Dave Gutzler presented. “One of the mistakes beyond simply overestimating the supply of water is underestimating the range of variability and the nature of the uncertainties,” he says. “We need to stop trying to figure out what the average is going to be and plan with a range of wet and dry scenarios in mind.”

Fleck ends where he began with another positive example of resilience planning and execution. He described a project in Las Vegas, NV and southern California jointly investing resources in a major wastewater reuse plant in southern California. He says because of it, southern California and Las Vegas are in great shape for a long time. “I think the water management community in both of those places would argue that they don’t need this extra water from this very expensive plant, but they’re investing now and planning now, and that’s what we need to do going forward.”

Panel: Science-Based Planning for Resilience

Resilience Begins with Data – Stacy Timmons

by Kathy Grassel

NM Bureau of Geology

Water data collection has always been hit or miss and often proprietary within the agencies collecting it, resulting in a patchwork of good data, hidden data, incomplete data, shoebox data and no data. Stacy Timmons, a hydrogeologist working at the NM Bureau of Geology at NM Tech, is determined to change all that by means of the Water Data Act, legislation that passed the legislature in 2019, pushed through by the tireless efforts of Rep. Melanie Stansbury and Rep. Gail Armstrong, that aims to bring all available water data together in a cohesive way. There are five agencies named with Timmons’ Bureau of Geology named as the convening group. “The major task is to make it so that we can share, integrate, and manage our water data. A really tricky work in that is ‘integrate,’” Timmons says. “We have a lot of data around the state that doesn’t all work well together. The key goal is making these data work together so we can think about how much water we have and how good that water is, so it’s not just one individual parameter by itself.”

Timmons clarifies the difference between data and information. People are looking for information. Data has got to be good quality before it goes into building an informational item. “Data are basically the building blocks, the Legos, the little bits and pieces that fit together to build something more useful,” she says. “Information is the interpretation–building a model, building maps, and making a report based on the data. What our community in the water world is looking for is information that we want to use to make our decisions, but they have to be based on solid data to begin with.”

All this data is destined to go into the new website, which she describes as an online catalog. The website newmexicowaterdata.org is purposefully not under any agency; you can see topics, actual data sets, links to where other data are located, another link to take you to reports. “We’re also working to develop a plan to deal with legacy data. In NM we have piles of data on paper, like shoeboxes under people’s desks,” she says. “We’re going to try to dig those out and make those relevant and useful.”

What can data do to build water resilience? Simmons cites two real-life examples that demonstrate ways that water data have been valuable in the world of actual resilience and water use. In 2004, issues came up in the Rio Hondo community near Taos. For years water management in this acequia community was done by eyeballing how much water was flowing through the acequias, leading to tremendous conflict in community meetings and after the meetings. It came to the point that people got together and agreed on a plan to install a plume and put on a real-time data collection device. “It had a pressure transducer and telemetry and the data were being shared in real time,” Timmons says. “Everybody started to see what exactly was flowing through the ditches and began to trust that their neighbor was getting an equal amount. It’s a small example of how data can be used to help build consensus and understanding—integral parts to having a water resilient future.”

Timmons tells a second story about the small community of Magdalena. In 2013 they were down to one single functioning well to supply the whole community and that well stopped working in June in the heat of the hot summer months. “Our agency along with other agencies was able to go there and help,” she says. “We measured water levels from our group and looked to see if there was a wholesale aquifer problem. As it turned out, it was not. We had data to show that there were some wells that were continuing to have a solid water supply.” By looking at the gallons per capita per day compared with previous years and the water level data and a number of other pieces, they could confidently assure the community that there were other water supplies. The community had been using a big tank and injecting into their hydrants to get water into their system. Soon after that, they got that one well back on line and were able to piece together enough funding to get two other wells on line. The community now continues to work with a handful of wells that are building resilience, building alternative sources, not just that one single well, so they have a more redundant water system. “On top of that, they were able to significantly reduce their water use, so their gallons per capita went from something like over 200 to less than 100 in the short period of time right after this happened,” she says. “All of this is basically a nice story of how data can be used for bettering a community. ”Timmons stresses that building water resilience means building redundancy and increasing flexibility and to do that you need to have water data to forecast future conditions to inform decision-making. “So as we begin to integrate our water data, a lot of these things will come to light.”

Panel: Science-Based Planning for Resilience

Late to the Game: A Native Perspective – Darryl Vigil

by Kathy Grassel

Jicarilla Apache Nation

Darryl Vigil’s talk about tribal participation and engagement was an eye-opener for anyone who took for granted that tribes were getting seats at the tables of water allocation policy decisions. Vigil is the Water Administrator for the Jicarilla Apache Nation. He is also the interim director of the Ten Tribes Partnership of the Colorado River, and holds other positions whose purpose is to ensure that tribes are finally included at the table.

Jicarilla has 6,000 acre-feet of historic rights, but also 40,000 acre-feet of water rights after the 1992 settlement with the federal government– 33,500 are stored at Navajo Dam, another 6,500 stored at Heron Dam. As are part of the San Juan Chama project, Jicarilla has ongoing leasing programs with PNM, the City of Santa Fe, Las Campanas, and oil and gas leases. Because Jicarilla’s settlement water is stored at Navajo Dam, geographically the tribe doesn’t have access to divert that water back onto the reservation, thus the majority of its settlement water is used for economic purposes, mostly in the form of these leasing provisions inside the settlement. “Navajo Dam is right at Four Corners,” Vigil says. “Now because of the shutdown of the coal-fired power generation in Four Corners, we absolutely have no market for the biggest chunk of our water.” In addition, because of Colorado River compact apportionments and the inability to move water across state boundaries, “for the last two years we’ve had about 30,000 acre-feet of water just go down the San Juan River into the Colorado River for free.” Vigil says because of the Law of the River, collectively a half-million acre-feet of unused tribal entitlements go down the river for free with no credit at all.

Now following eight years of stagnation with the previous administration, Vigil credits New Mexico’s new administration and “the fine folks at the OSE and ISC offices” with helping to make some headway in developing its water rights. “We’re also part of the Navajo Water Supply project,” he says. “We work closely with Navajo, with Jason John, about solutions to get water to To’Hajiilee.” [To’Hajiilee is a non-contiguous section of the Navajo Nation west of Albuquerque, formerly the Canoncito Indian Reservation.] Vigil also wishes to utilize existing creative partnerships with New Mexico’s state leadership to find ways to keep their water within the state boundaries.

Vigil goes into the history of why all this has been so difficult. It boils down to being late to the game. In the early 90s, 10 tribes along the main stem and the tributaries of the Colorado River settled their water rights with the federal government. “Now that we had these water rights, what were we going to do with them?” Vigil asked. “Remember the compact was enacted in 1922 and almost 70 years later we have a settlement. We’re late to the game in terms of layers and layers of policy that already existed before we even got in the game.” In 1992 the 10 tribes from the seven Basin States got together and formed the Ten Tribes Partnership of the Colorado River. “The significant thing about these 10 tribes is that cumulatively we have 2.8 million acre-feet of water rights, which is 20 percent of the volume of the Colorado River, and traditionally we’ve never had any access to any of those policy tables at all,” Vigil says. To address this one-sided reality, the member tribes in 1996 joined the Colorado River Users Association in hopes of actively participating with the seven Basin States in negotiations relating to the Colorado River. “We wrote a powerful vision statement expressing that the partnership will embrace and own the stewardship of the Colorado River and lead from a spiritual mandate to ensure that the river will always be protected and be available and sufficient for each tribe’s homeland,” Vigil says. “That’s what guides us.”

Time passes. In 2007 the Basin States and the Reclamation got together and created a set of interim guidelines for operations and management of the river. Again, tribes were not included in any policy discussions at all. Move ahead to 2012 when again the Basin States and the Bureau of Reclamation engaged in a supply and demand study. Again, tribes were not included or invited. When that basin study was released in 2012, one of the biggest findings was an imbalance of supply and demand of one million acre-feet, the imbalance projected to be three million acre-feet by 2016. “That should be pretty alarming,” says Vigil. “We jumped up and down, we demanded, we declared that the basin study did not adequately capture tribal water rights in this study.” So the tribes forged a partnership with Reclamation, which allocated resources to do a separate Tribal Water Study. It took five years to complete. It tells each tribe’s story individually and is based on scenario planning over 50 years where each tribe shows its current usage and potential for development. Importantly, it highlights issues of equity and social justice as related to tribes’ ability to develop their water rights.

“We’re having a basin-wide gathering this year. Because of climate change and other factors, the current system and structure of operation and management of the Colorado is not sustainable, thus tribes absolutely have to be at the table,” Vigil concludes. “I really think that there’s an opportunity to build a new paradigm of policy engagement, to create something that doesn’t exist right now, that incorporates tribal environmental and cultural values into policy. It’s something that hasn’t been done.” Vigil reminds us that tribes have been living sustainably and resiliently for thousands of years in this area and that they hold inherent understanding in designing water policy. If only we’d ask.