Confronting an Unprecedented Water Crisis

This February, Nature Climate Change published a study that found that the current drought in the U.S. West is the worst in twelve centuries. So indeed, the title of this year’s annual meeting “An Unprecedented Water Crisis: A Time to Act” was not an exaggeration or scare tactic. Despite this awful news, the good news from the meeting is that people all over the state are working to mitigate the impacts of a drying climate.

Contents

28th Annual New Mexico Water Dialogue Annual Meeting “An Unprecedented Water Crisis: A Time to Act” by Lucy Moore

Reflections on Finding Balance in Protecting Natural Resources by Representative Gail Armstrong

Surface Water: Vulnerable to a Changing Climate by Alan Klatt and Daniel Guevara

28th Annual New Mexico Water Dialogue Meeting

“An Unprecedented Water Crisis: A Time to Act”

by Lucy Moore

Déjà Vu All Over Again: The last paragraph of my article about last year’s New Mexico Water Dialogue (NMWD) looked forward to the January 2022 meeting and anticipated a hybrid event, where those lusting for Indian Pueblo Cultural Center enchiladas and chatting around the coffee urn could attend in person. However, with the arrival of a new COVID variant, by mid-year it was clear that our 28th annual would once again be virtual. As the Dialogue’s board began to develop the agenda, it was also clear that our water crisis was still with us, and that action was needed now more than ever.

I’m happy to report that, in spite of being relegated to our Zoom boxes, the results were gratifying. The Dialogue’s founding passion for bringing water users and managers together in respectful, honest dialogue prevailed. Over 165 registered and participated. A poll revealed that one-third were attending for the first time; half were between 40 and 60 years old, with the remaining split between 25-40 and over 60; the majority were from Albuquerque-Santa Fe, but there was representation from all quadrants of the state. The agenda offered plenty of opportunities for both informative presentations by key voices in the current water world and questions, comments, challenges and contributions by attendees.

2022: A Timely Partnership: With the state’s 50-Year Water Plan in development, this year’s meeting was a great opportunity to educate the public and hear their concerns and ideas for a more secure and equitable water future. The Dialogue board partnered with the N.M. Interstate Stream Commission (ISC) and the Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources for maximum benefit to the state effort. Rolf Schmidt-Petersen, Hannah Risely-White and Andrew Erdmann of the ISC, and Nelia Dunbar of the Bureau, helped with the planning and gave valuable presentations.

Virtual Lunch: A highlight of the in-person Dialogue is the lunch hour, a chance to chat with old and new friends. As facilitator, one of my most difficult challenges is tearing people away from those conversations…and the bread pudding. It’s clear that when people have a chance to spend unstructured time together, especially over food, they know what to do. They seize on an issue, a question, a worry, and take off, totally engaged. All, of course, are concerned about water, but each comes with a particular angle, a personal experience, a proposal to try out on others. It is important to give time and space for those conversations. So, this year we added a networking lunch on day one. Participants were invited to grab whatever lunch was at hand in their office or home and spend an hour or so at a “table” with others. The tables, of course, were Zoom breakout rooms of 6-8 randomly assigned participants. There were no instructions, no themes, no report-outs. You could spend it however you wished. Those who participated (about 75) gave rave reviews.

Keynote: Aaron Chávez, president of the NMWD board, introduced Mike Hamman, a fortuitous keynote choice for many reasons. As the governor’s senior water advisor, and recent director of the Middle Río Grande Conservancy District, he could offer the latest thinking on short- and long-term actions being considered to combat the impacts of climate change on the state’s diverse interests. And although no one knew it at the time, we were also hearing from the next state engineer. Later in the month, Hamman received that appointment.

“For Native communities, Water—with a capital “W”—is a family member, and should be valued and treated as such.”

– Kai-T Blue Sky (Cochiti Pueblo)

Equity, Justice and Legislative Action: Our next speakers focused on “Equity, Justice and Legislative Action in Times of Climate Change.” Dr. Karletta Chief, associate professor, Environmental Science at the University of Arizona, opened our eyes to climate impacts on tribal communities and the lack of infrastructure capacity to handle changes in quantity, quality and the timing of precipitation. Her photographs powerfully illustrated her remarks. Andrea Romero, N.M. state representative from District 46, Santa Fe County, previewed bills she planned to sponsor, including funding support for the Office of the State Engineer for water planning, administration and management, as well as support for the Acequia and Community Ditch Fund.

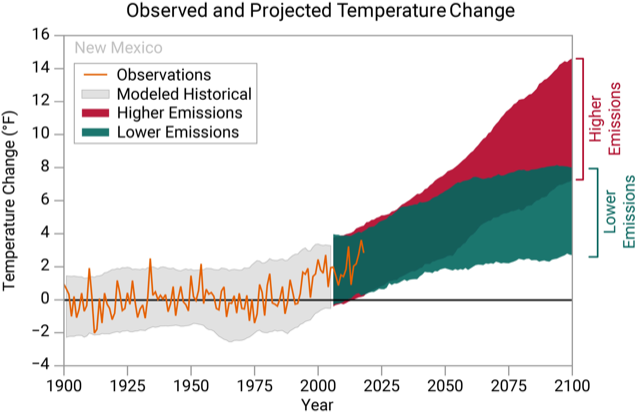

The NM State 50-Year Water Plan: Three panelists focused on the role of the state’s 50-Year Water Plan. ISC Director Rolf Schmidt-Petersen shared the governor’s goals for the plan as well as her vision for building water resilience through sustainability and equity. He and the governor are committed to helping all citizens understand the impacts of climate change and how to mitigate it by making the plan relevant and accessible for everyone. Nelia Dunbar, state geologist and director of the Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, explained the role of research experts in informing the 50-year planning process. Their tall order was to “assess and synthesize recent scientific literature on climate, hydrology and the impacts of these changes” on N.M., projecting 50 years into the future. The science, she said, is conclusive: the atmosphere is storing more heat and driving up the temperature. The outcome is up to us. N.M. State Sen. Liz Stefanics urged everyone to take action in whatever way they can. A cornerstone of democracy, she said, is citizen participation. If we want to see change, now is the time to start talking, talking to our family, friends, community and legislators.

Water Survey Overview: Nina Carranco and Patrick McCarthy, speaking for the Water Foundation and the Thornburg Foundation, gave hot-off-the-press results of a statewide water survey of 706 people, representing a diverse cross-section—private-public, urban-rural, tribal, etc. Respondents were also across the political spectrum. Results reflect strong bi-partisan support for adequate river flows; safe, affordable drinking water; water for agriculture and wildlife; water recycling; infrastructure; sustainability; and public access to water data.

“Our values are expressed through our actions, and all the critical issues we face are symptomatic of our actions.”

– Jeffrey Samson (NMWD Vice-President)

Day Two: Day two began with an inspiring welcome from Jeffrey Samson, vice president of the NMWD board. Samson reminded us of a message from last year’s panelist, Kai-T Blue Sky from Cochiti Pueblo. For Native communities, he said, Water—with a capital “W”—is a family member, and should be valued and treated as such. Samson noted that our values are expressed through our actions, and that all the critical issues we face are symptomatic of our actions. He quoted the late local hip-hop artist and activist, Andrew “Wake Self” Martínez, “We forget that our bodies are water, while we pollute bodies of water.” But change is on the horizon, he concluded, “with conversations like ours happening all over the world.”

The first speaker, professor Sam Fernald, director, N.M. Water Resources Research Institute, zoomed in from London to give us highlights from the recent 66th annual WRRI conference.

Communities’ Resilience: The panel that followed offered lessons learned about communities’ resilience, or as speaker Jason John said, “the ability to bounce back into shape.” John, director of the Navajo Department of Water Resources, used the response to COVID to illustrate that Navajo resiliency is rooted in family, yet dependent on external support. Grace Haggerty, senior hydrologist/program manager at the ISC, illustrated resiliency with a cycle schemata based on experiences throughout N.M. communities. Mary Kelley, partner with Culp and Kelly in Arizona, gave highlights of strategies for forest management restoration, including adaptation, reduction, mitigation and strengthening. Kevin Moran, senior director, Water Policy and State Affairs, Environmental Defense Fund, described Water for Arizona Coalition efforts to develop strategies to manage groundwater for a water-scarce future. The coalition depends on a common agenda, organizations that can support the work, good communication and regular evaluations.

“Shortage-sharing agreements are good adaptation tools, but call for serious cooperation among neighboring water interests.”

– Frank Scott, Pecos River Bureau Chief, Interstate Stream Commission

Adaptation Strategies: The last panel included Aron Balok, superintendent, Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District; Carolyn Donnelly, Water Management and Operations manager, Bureau of Reclamation (BOR); and Frank Scott, Pecos River bureau chief, ISC. Balok shared the challenges of meeting the delivery requirements of the Pecos Compact and the benefits coming from the settlement agreement, which administers rights in the basin, an alternative preferable to the potential economic devastation of a priority call. The agreement also limits pumping from wells and tests the condition of the aquifer on a daily basis. Scott highlighted the value of shortage-sharing agreements, which are good adaptation tools, but call for serious cooperation among neighboring water interests. The good conversations that ensue are important, he added. Donnelly spoke of BOR’s predictions for serious shortfalls in the Río Grande in coming months and potential strategies to increase storage capacity in reservoirs.

REPORTS FROM BREAK OUT GROUPS

Participants Take the Stage: Eileen Dodds, NMWD secretary-treasurer, kicked off a Dialogue tradition, “Table Talks,” or in this case, Zoom breakout rooms. Attendees could use their own experience and expertise to look at climate change impacts and adaptation strategies, while providing valuable feedback to the ISC on the seven topics drawn from the state’s 50-year water plan. For each topic the assignment was to identify impacts from climate change and offer strategies to deal with those impacts. Many of the impacts, they noted, may not be directly the result of climate change (now and in the future) but will be worsened by it if action is not taken. Highlights from the report-outs follow:

Ecological Impacts and Strategies: (2 groups)

Threat to instream flows from competing demands

- Inventory streams to prioritize restoration efforts on public and private lands

- Consider ecological offsets for water leases/rights for ecologically harmful uses

- Change the N.M. Constitution to omit “unappropriated” from “all unappropriated waters belong to the people of N.M.”

- Develop policies to keep water in-stream for environmental flows.

- Aridification of air and soil on high elevation forests

- Focus on climate change and sustainability in restoration project plans

- Access new federal funding and state tech support for ecologically based projects (Forest Action Plan).

- Reintroduce fire to open the canopy for more snow on forest floor; reduce risk of large high-severity fires; help trees resist beetles and fire (“keystone disturbance”).

Lack of awareness among public and policy makers

- Support and utilize local protection and restoration knowledge; increase local technical capacity

- Educate students throughout the state on natural and water resources stewardship.

- Create N.M. Water Resources Department to centralize all water-related state offices.

Dry Rivers

- Educate legislators on water issues

- Bring all voices to collaborate on river management.

- Reduce consumption across the board.

Depleted aquifers

- Allocate permanent funding for state Water Data Act.

- Coordinate use of surface and groundwater (conjunctive use).

- Recharge aquifers with treated water.

- Find lessons, ideas in other states.

Agricultural Impacts and Strategies (2 groups)

Competition between agricultural and domestic uses

- Allow fields to go dry (water fallowing).

- Understand the ecological values of agriculture: urban green space, carbon suppression, wildlife habitat, ecosystem

Depletion—mining water

- Support conservation easements and lease agreements.

- Plant dryland crops.

- Monitor and care for soil health and moisture containment.

Watershed and rangeland management—assess old management systems

- Learn from farmers and ranchers what works on the ground.

- Increase water infiltration in soil and aquifers.

- Design a process for all stakeholders to contribute, listen and leave their egos at home.

The Collective Good—inability of many to listen and compromise

- One-size and top-down doesn’t work; the top needs to know what’s happening on the ground.

- Set up stakeholder working groups by regions, use water budgets, integrate with state socio-economic management goals

Water Quality Impacts and Strategies

Funding—There is a need to ensure that quality gets its share.

- Secure federal funding for water-quality initiatives.

- Make regulatory changes to connect water quantity and quality agencies and promote collaboration, with linked funding.

Salinity

- Coordinate surface and groundwater use (conjunctive use)

- Regulate potash mines

- More comprehensive monitoring of water resources and groundwater pumping

- Colorado Salinity Forum is a good model.

Culture and Tradition Impacts and Strategies

Lack of recognition of the Indigenous perspective on climate change and water.

- More space for community-to-community conversations

- More recognition and inclusion of community perspectives in wide variety of forums, not just with government agencies

Growing need to recognize the rivers as living beings, in ecological and spiritual contexts

- Promote rights for rivers

- Respect what rivers need to promote and sustain future generations

Broken relationships between communities around water issues

- Build relationships and trust with conversations that include all perspectives.

Public Water Systems (PWS) Impacts and Strategies

Financial capacity—The vast majority of community water systems serve fewer than 5,000.

- Prioritize capacity-building for operational and maintenance needs of smaller water systems to give them equal weight to large systems.

- Work to provide long term federal or state funding for local and tribal systems.

Technical capacity—not enough certified public water operators

- Make water operator careers attractive and accessible for young people.

- Use “Help N.M.” (Workforce Solutions) fund operators.

- Highlight the need for water operators in the 50-Year Water Plan.

- Highlight success stories—Navajo Nation Department Water Resources investment in incentivizing water operations careers for youth

Managerial capacity—how to make sure we have water where we need it

- PWSs can share resources and equipment (bookkeeper, backhoe, operators, etc.).

- PWSs can do creative water rights sharing.

- Outreach for reuse can work on very small scale—gray water to landscape, etc.

Economic and Recreational Impacts and Strategies

Influx of funding—need to be sure it’s equitably distributed

- Create process for all interests to meet, discuss intrinsic values of water, including non-market

- All water needs are intertwined—agriculture, wildlife, recreation, urban, rural, commercial

Rural and natural areas “loved to death” lose their value as an asset for recreation.

- Advocate for adequate funding for agencies to address impacts of overuse.

- Encourage planning from below.

- Prioritize data gathering; good decisions need good data.

Competition with other uses for water

- Create “Roundtable” based on Colorado model, where people can listen, find solutions together and break down silos of interests.

- Advocate for policies that help communities protect and manage their resources.

Hydrologic Processes Impacts and Strategies

Soil condition—damage from fire, drought, temperature, pollution, erosion

- Improve herbaceous and shrub layer ground cover, statewide.

- Help ranchers and the agricultural community improve soil condition.

Stream and headwaters degradation—need to restore and protect

- Minimize red tape for restoration projects.

- Bank storage; floodplain as a sponge; aquifer monitoring; reconnect streams

- Sustainable rangeland management

Lack of awareness, concern, political will—education and outreach

- Clear messaging (fact-based and heartfelt), authentic delivery

- Engaging communication strategies (advertising, campaigns, etc)

- Build community

Wrapping It Up: We wish to thank the volunteer facilitators and note-takers from agencies, organizations and just plain people who shepherded the groups through the discussions. Their rich summaries were passed on to the Interstate Stream Commission for consideration as they develop the 50-Year Water Plan. Speaking of which, dare we look ahead to January 2023 and invite you to join us at the Pueblo Cultural Center? Let’s hold that vision and hope for the best.

Lucy Moore is one of the founders of the New Mexico Water Dialogue and facilitates the NMWD’s annual statewide meetings and many other events. https://nmwaterdialogue.org. A similar version of this article was written for the March/April issue of the Green Fire Times (www.GreenFireTimes.com).

The Water Dialogue thanks the following:

The Interstate Stream Commission for partnering with the New Mexico Water Dialogue and the Water Resources Research Institute in reaching out to the public.

Speakers Mike Hamman, Dr. Karletta Chief, Representative Andrea Romero, Rolf Schmidt-Petersen, Nelia Dunbar, Senator Liz Stefanics, Sam Fernald, Grace Haggerty, Jason John, Mary Kelly, Kevin Moran, Aron Balok, Carolyn Donnelly, Frank Scott.

Also special thanks to Lucy Moore, Sophia Cinnamon, Virginie Pointeau and Jeffrey Samson for all the work it took to run the meeting.

And thank you all who attended the meeting and contributed to planning for a dryer climate.

For those who are interested, the following are available online.

- Welcome from President Aaron Chavez

- Welcome from Vice-President Jeffrey Samson

- Recording of the event

- Copies of presentations

- Chat

- Break Out Groups Summary

- “From the Chat: Recommended Resources”

Reflections on Finding Balance in Protecting Natural Resources

by Representative Gail Armstrong

For those of us who grew up in the desert southwest, you learn at an early age that water is the “life blood” of this great state of ours. As a rancher these past several years of drought have resulted in a renewed commitment to being stewards of the land. As a State Representative elected to represent my district, I am committed to fighting to protect all of our natural resources with the conservation and preservation of water at center stage.

It’s time we balance the emotional and often times radical narrative with a rational, common sense approach to developing solutions. We owe it to our kids and grandkids to preserve and protect this way of life that sustained so many generations before ours.

I believe that civility will be foundational to our approach. Weather working across the fence with our neighbors or working across the aisle in Santa Fe, we will get more accomplished working together.

Big thank you to the Hanuman Foundation for their continuing support!!!

Surface Water: Vulnerable to a Changing Climate

by Alan Klatt and Daniel Guevara, New Mexico Environment Department, Surface Water Quality Bureau

Ecological resilience can be broadly defined as the ability of an ecosystem to withstand a disturbance, either from natural or human causes, and thereby self-maintain its inherent structure and function. There is always a concern that too great of a disturbance can cause an irreversible shift, with potentially harmful consequences. Human activities, through greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, are affecting natural systems and posing significant risks to human health and our natural and cultural heritage (Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, Executive Order 2019-003).

Dr. Bruce Thomson, Regents Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of New Mexico, recently drafted a chapter in the Interstate Stream Commission’s Leap Ahead Analysis Assessment for New Mexico’s 50-Year Water Plan update. In it, Dr. Thomson writes that surface-water resources are especially vulnerable to the effects of a warming climate, as both the quantity and quality of the resource may be negatively impacted by a warming climate. Lower flows, that are slower and warmer, will result in increased E. coli concentrations which will correspond to increased threats to human health. Those same lower and warmer flows will hold less dissolved oxygen which is harmful to aquatic organisms because low oxygen levels affect metabolism, behavior, and mortality. Already, New Mexico has over 2,100 miles of streams that exceed their water quality standard for surface water temperature – the temperature that is needed to meet the designated use of our public waters to support aquatic life. Endangered western native trout cannot survive in waters where maximum temperatures consistently exceed 21-22 degrees Celsius (69.8-71.6 degrees Fahrenheit) even though they may be able to tolerate brief daily periods of higher temperatures.

But it’s not too late! The state of New Mexico is taking action to protect human health and our natural and cultural heritage. Collaborating and partnering with stakeholders across the board, we are reducing GHG emissions and identifying other climate adaption and mitigation strategies. The state’s Climate Change Task Force is outlining the necessary steps, a path forward, that will help us adapt and create a more secure future. One strategy is to increase the resiliency of natural systems. Doing so will help us respond to the warming we are currently seeing and will also help us better prepare for the continued warming we expect to see in the future. Our natural systems face many disturbances or stressors, not just climate change, which can have compounding effects, so addressing those other stressors may help attenuate and lessen some of the impacts associated with climate change. The Surface Water Quality Bureau’s Section 319 Success Stories show us that we can restore our watersheds and improve water quality, and restored watersheds have greater resiliency.The newest upcoming New Mexico 319 Success Story is at San Antonio Creek in the Valles Caldera National Park, where changes in land management and decades of restoration work is yielding improvements to water quality. Restoration efforts have included changes to grazing management, floodplain reconnection, erosion reduction, and preserving and enhancing wetlands. Monitoring by SWQB staff demonstrates that these treatments are having a desirable affect in reducing stream temperatures, reducing turbidity, and improving aquatic habitat. All of these add up to increased resiliency for San Antonio Creek and a healthier and more prosperous New Mexico for present and future generations.