Groundwater: A Declining Resource

Drought and climate change and their impacts on surface water are in the news. What is not in the news is the related crisis associated with groundwater. This problem is impacted by both less surface water, but also by a resource that is increasingly inadequate to meet the needs of those who rely on groundwater, especially when there is no rainwater to supplement ground water supplies. This issue has two articles: an overview of groundwater in the U.S. that includes a strategy for protecting this resource by Holly Richter as well as a look at how important groundwater is to New Mexicans by Kate Zeilger.

Contents

Expanding the Toolbox for Replenishing Groundwater

Holly Richter

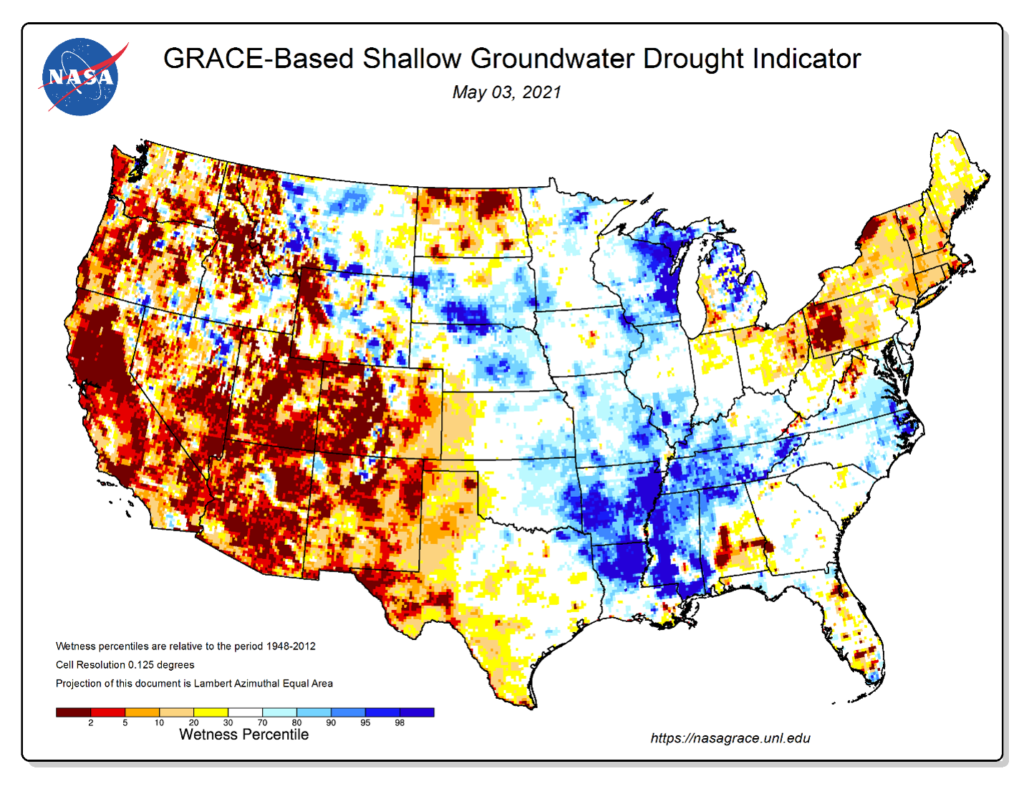

Water is the lifeblood of the arid West. While we have all seen the photographs of places like Lake Mead with telltale bathtub rings that reflect declining water levels, the declines beneath our feet in groundwater storage are much harder to appreciate. The U.S. Drought Monitor map below shows how much of the nation was experiencing severe, extreme, or even exceptional drought in terms of groundwater supplies as of early May.

In the United States, groundwater is the source of drinking water for about half the total population and nearly all of the rural population, and over 40 percent of irrigation water is groundwater. However, groundwater pumping remains largely unregulated in most western states, and groundwater, which has served as our safeguard when surface water supplies run short, has itself diminished over the past century.

More frequent and intense droughts, combined with population growth and aging water infrastructure, are not only increasing the potential for conflict over water resources, but also reducing water security, especially in the arid West. These urgent drivers, informed by the development of new science and technical tools, now encourage innovation and new approaches to our water management practices, policies, and projects as well as additional investments in western water infrastructure.

These investments can be most effectively leveraged by the incorporation of natural infrastructure approaches in combination with traditional approaches- it need not be an “either – or” choice. Natural systems are often overlooked in terms of their ability to assist with conveying and storing additional water at the right times, and in the right places, to help meet the multiple needs of both nature and people.

Replenishing groundwater storage can be accomplished in a surprising number of ways, through use of traditional and natural infrastructure, or better yet, a combination of both.

Put simply, “natural infrastructure” involves a natural system that is intentionally managed to provide multiple benefits for the environment and human well-being by conveying and/or storing water. Natural infrastructure storage solutions more specifically increase water storage through aquifer recharge, floodplain storage, or the alteration of the timing of runoff. These solutions mimic natural riverine, wetland, ecosystem, or hydrologic processes, which in many cases also provide added benefits to the environment and recreation. New methods to evaluate the costs and benefits of natural infrastructure for aquifer recharge, as well as their return on investment, have been developed to prioritize investments and decision-making.

Replenishing groundwater storage can be accomplished in a surprising number of ways, through use of traditional and natural infrastructure, or better yet, a combination of both. Different types of landscapes offer different opportunities for replenishing groundwater aquifers. How we manage our watersheds above ground—the conditions of woodlands, forests, grasslands and deserts–can affect how rainfall enters and moves through natural systems, ultimately determining how much natural runoff, groundwater storage and/or streamflow occur. But what if existing recharge rates aren’t enough to satisfy our water demands in the 21st century?

There are a variety of approaches that have been undertaken to advance innovation in natural storage solutions. Some of the best solutions come from the local level where customized solutions are developed according to context and specific need. These approaches can range from managed aquifer recharge (MAR) of treated effluent or stormwater, to floodplain restoration, beaver reintroduction and even irrigation methods that enhance recharge. Aquifer storage can be more sustainable and cost-effective than traditional gray infrastructure alone, and these projects have the potential to build adaptive capacity in ecosystems, ranching operations and rural communities, as well as large metropolitan areas, to help deal with ongoing climate shifts. They can improve watershed resilience, support floodplain functions, improve stream flows, provide habitat, minimize erosion and sedimentation, and support recovery from extreme natural events such as droughts, floods, and fires.

I recently testified at a U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Subcommittee hearing on natural groundwater storage solutions, and provided some specific examples, here is the full hearing and my written testimony.

Drought and Groundwater Challenges in Rural New Mexico: Thoughts from Northeastern New Mexico

Kate Zeigler

For most of northeastern New Mexico, there is little to no surface water unless you’re lucky enough to live up in the mountains. And even there, as the drought deepens, the streams and creeks (and their dependent acequias) are drying up. Much of the region, primarily rural agricultural communities centered around cattle ranching and small-scale farming, is thus entirely dependent on groundwater. However, unlike a stream where you can see the flow of water declining, groundwater is effectively invisible. Without being able to see the “bathtub” a well draws from, it’s nearly impossible to know if your well is destined to serve you and your needs for many years, or if you’re on the brink of disaster. As the drought continues, seemingly unending, those who have traditionally been reliant on surface water, including the acequia systems, are finding themselves having to turn towards their wells (if they have them) or trying to navigate the world of drilling a well and becoming groundwater reliant. Those who were already dependent on well water are having to draw even harder on that resource to sustain themselves and their livelihood, which is the economic backbone of the region.

Without being able to see the “bathtub” a well draws from, it’s nearly impossible to know if your well is destined to serve you and your needs for many years, or if you’re on the brink of disaster.

As more folks tap into that invisible resource, the aquifers are declining and have been for some time. Some are failing more rapidly than others, but the overall pattern in northeastern and eastern New Mexico is of overall loss of this resource. Wells that have shallow water tables and are near points of recharge get no reprieve – there’s no surface water to help boost those shallow aquifer systems. In addition, with dropping water tables come issues with water quality as salts accumulate, creating health problems for humans and livestock, and harming planted crops. Many of the rural agricultural communities are facing the loss of land held for generations that is the heart and soul of so many families in the region. As wells fail, where do we go? Deeper is not always a viable option as a) there may not be any water-bearing zones within a drillable distance, b) deeper water is frequently salty or has other water quality issues and/or c) deeper waters are even less likely to receive recharge so we’ve really just kicked the can down the road. Do we abandon the region? How do we assimilate these people into urban areas that are equally strapped for water resources? How do we cope with the loss of communities and the traditions that have grown around them over decades to centuries? Many are already turning to a variety of conservation methods, including the lost art of grazing management to help improve soil health and infiltration, as well different cropping techniques and strict management of every drop at the well itself. Certainly, there is no easy, quick fix, but we cannot leave the rural communities behind as we seek to navigate these challenging, changing times.